Is It Art Or Is It Science?

Is It Art Or Is It Science?

Photography means different things to different people.

Art, according to the Oxford Dictionary, is “the expression or application of human creative skill and imagination… producing works to be appreciated primarily for their beauty or emotional power.”

Science, on the other hand, is “the intellectual and practical activity encompassing the systematic study of the physical and natural world through observation and experiment.”

Look closely at those definitions and a few words leap out. If we combine them, could we say that photography is an intellectual and practical activity that produces work to be appreciated for its beauty or emotional power? If so, then photography is not forced to choose a camp. It is both Art and Science.

Everyone has a camera now, and the world is drowning in images—endless streams of snapshots created through constant, thoughtless activity. But most of these photographs have no beauty, no emotional pull, no real connection. They simply exist, flat and forgettable.

Why?

Because they’re missing the crucial ingredient: thought.

The intellectual spark.

The part that gives purpose to the practical act of pressing the shutter.

Social media and its avalanche of bland imagery have numbed us. Our standards for what makes a “good” photograph—one with genuine aesthetic appeal or emotional resonance—have eroded. High contrast tricks the eye. Heavy saturation masquerades as creativity. A million selfies, countless vacant sunsets, and platefuls of someone else’s dinner flood our vision until nothing stands out.

We can, and should, aim higher.

When we put intention behind our photography, we shift from taking a photo to making one. To strengthen that intention, we must observe and experiment.

Observation works in two directions.

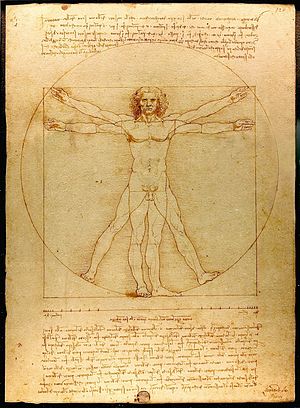

First, observe the external. Spend time with paintings—especially those by great artists such as van Gogh, Rembrandt, Michelangelo, Monet. Look at the work of influential photographers like Edward Weston, Ansel Adams, David Bailey, Vivian Maier. Study the iconic images that helped shape history. Wander through galleries, physical or virtual, and pay attention to shapes, perspectives, colours, angles, lines, composition, light, shadow—and above all, notice how each piece makes you feel.

Then observe the internal—your own creative instincts. Practise. As you move through the world, notice the quiet details: the curve of a shadow on a pavement, the way morning light glances off a window, the geometry of buildings, the rhythm of colour in a crowded street. Tune into what makes you pause. What stirs something in you. What makes you feel.

Next, experiment.

When a scene grabs you—even subtly—photograph it. More than once. Try different angles, different distances, different ways of interpreting what caught your eye. Then look at those images with honesty. Which ones truly express what you saw or felt? Which ones fall flat? Which ones surprise you?

Through observing, experimenting, and practising with purpose, your intellect starts shaping your creative instinct. You begin to make photographs that are beautiful, meaningful, emotional—photographs with artistic weight that rise above the gazillion forgettable ones.